Elementare Musik: Interaktives Periodensystem wandelt He, Fe, Ca in Do, Re, Mi um

W. Walker Smith und Alan Parker

Wir alle kennen die Elemente des Periodensystems, aber haben Sie sich jemals gefragt, welches Element beispielsweise Wasserstoff oder Zink sein könnte? Stimme Likes? W. Walker Smith, jetzt Doktorand an der Indiana University, hat seine beiden Leidenschaften für Chemie und Musik kombiniert, um ein neues audiovisuelles Werkzeug zur Vermittlung von Konzepten der chemischen Spektroskopie zu schaffen, wie er es nennt.

Smith lieferte seine Daten Beschallung Das Projekt – das im Wesentlichen die sichtbaren Spektren der Elemente des Periodensystems in Schall umwandelt – ist diese Woche auf dem Treffen der American Chemical Society in Indianapolis, Indiana. Smith zeigte während seiner Show „Sound of Molecules“ sogar Soundclips von einigen der Elemente, zusammen mit „Strukturen“, die größere Partikel enthalten.

Als College-Student „I [earned] Doppelabschluss in Musikkomposition und Chemie, daher war ich immer auf der Suche nach einer Möglichkeit, meine Chemieforschung in Musik umzuwandeln.“ Smith sagte während einer Pressekonferenz. „Am Ende stolperte ich über die visuellen Spektren der Elemente und war überwältigt, wie schön und unterschiedlich sie alle aussahen. Ich dachte, es wäre wirklich cool, diese visuellen Spektren, diese schönen Bilder, in Klang zu verwandeln.“

Wie sehen die Artikel aus?

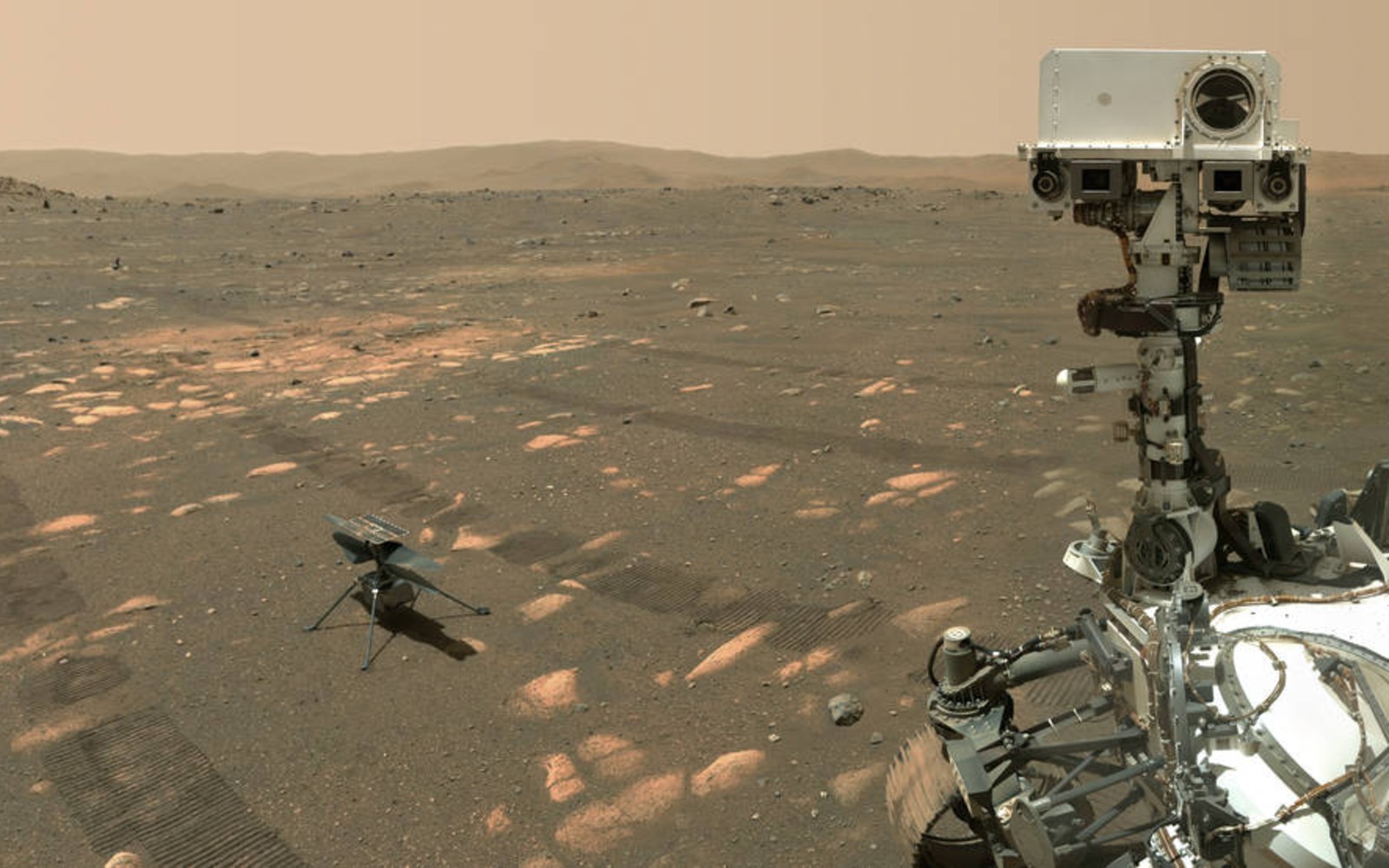

Datenbeschallung ist kein neues Konzept. Im Jahr 2018 veränderten Wissenschaftler beispielsweise ein NASA-Bild des Rovers Mars Opportunity im Jahr 5000j Sonnenaufgang auf dem Mars in der Musik. Die Daten der Teilchenphysik Es wurde verwendet, um das Higgs-Boson zu entdecken, die Echos eines Schwarzen Lochs, das einen Stern verschlang, und Magnetometer-Messwerte von der Voyager-Mission wurden ebenfalls in Musik umgewandelt. Vor einigen Jahren hat A.J[[“ embedded=““ url=““ link=““ data-uri=“d71e3e53769b46aa75512f689b034f33″>project called LHCSound built a library of the “sounds” of a top quark jet and the Higgs boson, among others. The project hoped to develop sonification as a technique for analyzing the data from particle collisions so that physicists could “detect” subatomic particles by ear.

Markus Buehler’s MIT lab famously mapped the molecular structure of proteins in spider silk threads onto musical theory to produce the „sound“ of silk in hopes of establishing a radical new way to create designer proteins. The hierarchical elements of music composition (pitch, range, dynamics, tempo) are analogous to the hierarchical elements of protein structure. The lab even devised a way for humans to „enter“ a 3D spider web and explore its structure both visually and aurally via a virtual reality setup. The ultimate aim is to learn to create similar synthetic spiderwebs and other structures that mimic the spider’s process.

Several years later, Buehler’s lab came up with an even more advanced system of making music out of a protein structure by computing the unique fingerprints of all the different secondary structures of proteins to make them audible via transposition—and then converting it back to create novel proteins never before seen in nature. The team also developed a free Android app called the Amino Acid Synthesizer so users could create their own protein „compositions“ from the sounds of amino acids.

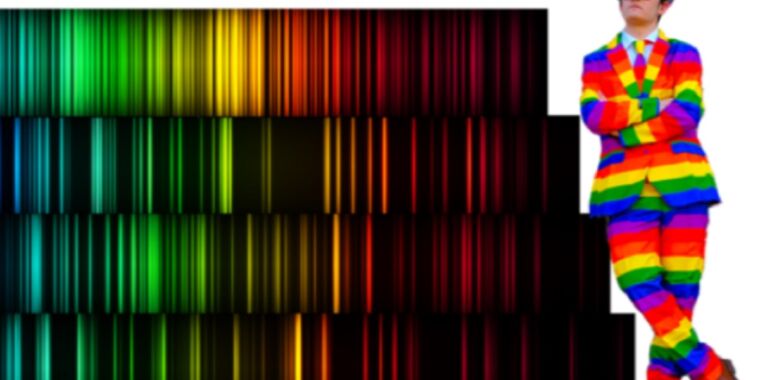

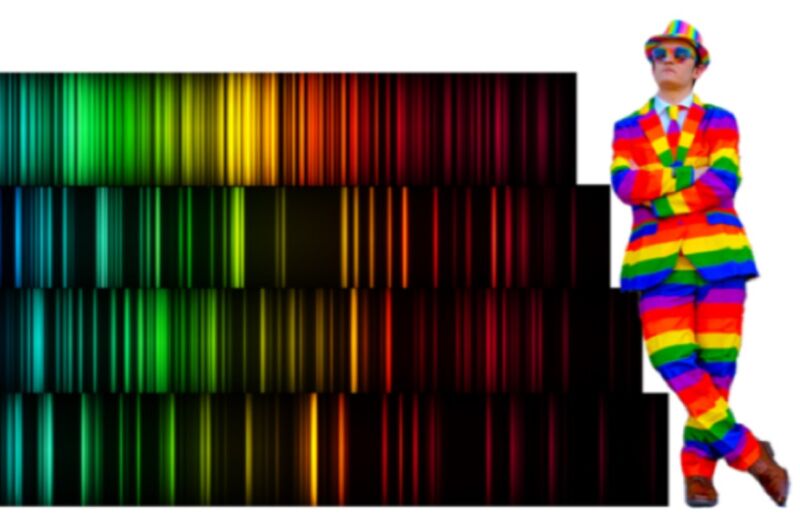

So Smith is in good company with his interactive periodic table project. All the elements release distinct wavelengths of light, depending on their electron energy levels, when stimulated by electricity or heat, and those chemical „fingerprints“ make up the visible spectra at the heart of chemical spectroscopy. Smith translated those different frequencies of light into different pitches or musical notes using an instrument called the Light Soundinator 3000, scaling down those frequencies to be within the range of human hearing. He professed amazement at the sheer variety of sounds.

„Red light has the lowest frequency in the visible range, so it sounds like a lower musical pitch than violet,“ said Smith, demonstrating on a toy color-coded xylophone. „If we move from red all the way up to violet, the frequency of the light keeps getting higher, and so does the frequency of the sound. Violet is almost double the frequency of red light, so it actually sounds close to a musical octave.“ And while simpler spectra like hydrogen and helium, which only have a few lines in their spectra, sound like „vaguely musical“ chords, elements with more complex spectra consisting of thousands of lines are dense and noisy, often sounding like „a cheesy horror movie effect,“ according to Smith.

His favorites: helium and zinc. „If you listen to the frequencies [of helium] Eine nach der anderen statt alle auf einmal, sagte Smith, Sie können ein interessantes Skalenmuster erhalten, das ich verwendet habe, um mehrere Kompositionen zu komponieren, einschließlich „Helium Dance Party“. Was Zink betrifft, so klingt die erste Reihe von Übergangsmetallgittern sehr komplex und dicht. Aber Zinc klingt aus irgendeinem Grund trotz seiner Fülle an Frequenzen wie ein engelhafter Sänger, der Vibrato singt. „

Smith arbeitet derzeit mit dem Wonder Lab Museum in Bloomington, Indiana, zusammen, um eine Museumsausstellung zu entwickeln, die es den Besuchern ermöglicht, mit dem Periodensystem zu interagieren, Klagen zu hören und aus den verschiedenen Klängen ihre eigenen musikalischen Kompositionen zu erstellen. Hauptsache ich will [convey] ist, dass Wissenschaft und Kunst gar nicht so verschieden sind. „Ihre Kombination kann zu neuen Forschungsfragen führen, aber auch zu neuen Wegen, um zu kommunizieren und ein größeres Publikum zu erreichen.“

„Musikfan. Sehr bescheidener Entdecker. Analytiker. Reisefreak. Extremer Fernsehlehrer. Gamer.“